Untergruppen, Untergruppenkriterien: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

*m.g.* (Diskussion | Beiträge) (→Gegenbeispiel) |

K (→Zeigen, dass e \in U) |

||

| (13 dazwischenliegende Versionen von einem Benutzer werden nicht angezeigt) | |||

| Zeile 138: | Zeile 138: | ||

====Gegenbeispiel==== | ====Gegenbeispiel==== | ||

Die Menge aller Spiegelungen bildet bzgl. der NAF keine Untergruppe der Gruppe der Bewegungen. | Die Menge aller Spiegelungen bildet bzgl. der NAF keine Untergruppe der Gruppe der Bewegungen. | ||

| − | ==Gegenbeispiel== | + | ==Gegenbeispiel 1== |

Wir betrachten <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \oplus ]</math> und <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \otimes ]</math>. Da wir bei multiplikativen Restgruppen das neutrale Element bezüglich der Restklassenaddition nicht berücksichtigen ist die Menge der multiplikativen Restklassengruppe modulo <math>7</math> eine echte Teilmenge der additiven Restklassengruppe modulo <math>7</math>. In beiden Fällen handelt es sich um Gruppen, <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \otimes ]</math> ist jedoch keine Untergruppe von <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \oplus ]</math>. | Wir betrachten <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \oplus ]</math> und <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \otimes ]</math>. Da wir bei multiplikativen Restgruppen das neutrale Element bezüglich der Restklassenaddition nicht berücksichtigen ist die Menge der multiplikativen Restklassengruppe modulo <math>7</math> eine echte Teilmenge der additiven Restklassengruppe modulo <math>7</math>. In beiden Fällen handelt es sich um Gruppen, <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \otimes ]</math> ist jedoch keine Untergruppe von <math>[\mathbb{Z}_7, \oplus ]</math>. | ||

| + | ==Gegenbeispiel 2== | ||

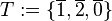

| + | <math>[\mathbb{Z}_4, \oplus ]</math> ist bekannterweise eine Gruppe. <math>[T, \oplus]</math> mit <math>T:=\{\overline{1}, \overline{2}, \overline{0}\}</math> ist keine Untergruppe von <math>[\mathbb{Z}_4, \oplus ]</math>, weil <math>[T, \oplus]</math> keine Gruppe ist. | ||

| + | =Definition des Begriffs Untergruppe= | ||

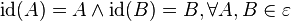

| + | ==Definition: (Untergruppe)== | ||

| + | ::Es sei <math>[G, \circ]</math> eine Gruppe und <math>U</math> eine Teilmenge von <math>G</math>. <math>[U, \circ ]</math> ist Untergruppe von <math>[G, \circ]</math>, wenn <math>[U, \circ]</math> selbst Gruppe ist. | ||

| + | ==Satz: (triviale Untergruppen)== | ||

| + | ::Jede Gruppe hat wenigstens zwei Untergruppen: Sich selbst und die Untergruppe die nur aus dem Einselement der Gruppe besteht. | ||

| + | =Untergruppenkriterium 1= | ||

| + | ==Satz: (Untergruppenkriterium 1)== | ||

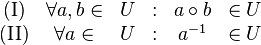

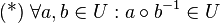

| + | ::Es sei <math>[G, \circ]</math> eine Gruppe und <math>U \subseteq G</math>. <math>[U, \circ]</math> ist genau dann Untergruppe von <math>[G, \circ]</math>, wenn: | ||

| + | :::<math> | ||

| + | \begin{matrix} | ||

| + | \text{(I)} & \forall a,b \in &U & : & a \circ b &\in U \\ | ||

| + | \text{(II)} & \forall a \in &U & : & a^{-1} &\in U | ||

| + | \end{matrix} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | =Untergruppenkriterium 2= | ||

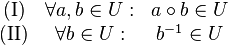

| + | ==Satz (Untergruppenkriterium 2)== | ||

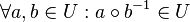

| + | ::Es sei <math>[G, \circ]</math> eine Gruppe und <math>U \subseteq G. ~</math> <math>~[U, \circ]</math> ist genau dann Untergruppe von <math>[G, \circ]</math>, wenn: | ||

| + | :::<math> | ||

| + | \forall a,b \in U : a \circ b^{-1}\in U </math> | ||

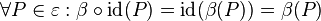

| + | ==Beweis von UGK 2== | ||

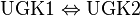

| + | Wenn UGK1 bewiesen wurde (was keine Schwierigkeit darstellt) reicht es zu zeigen, dass <math>\text{UGK1} \Leftrightarrow \text{UGK2}</math> gilt.<br /> | ||

| + | ===<math>\rightarrow</math>=== | ||

| + | trivial | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===<math>\leftarrow</math>=== | ||

| + | Es sei <math>[G, \circ]</math> eine Gruppe mit Einselement <math>e</math>. <math>U \subseteq G</math>. | ||

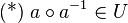

| + | ====Voraussetzung==== | ||

| + | <math>\text{(*)}~\forall a, b \in U: a\circ b^{-1}\in U</math>. | ||

| + | ====Behauptungen==== | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{matrix} | ||

| + | \text{(I)} & \forall a, b \in U: & a \circ b \in U \\ | ||

| + | \text{(II)} & \forall b \in U: & b^{-1} \in U | ||

| + | \end{matrix} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | ====Beweis==== | ||

| + | =====Zeigen, dass <math>e \in U</math>===== | ||

| + | <math>\text{(*)}</math> sagt aus, dass mit <math>a</math> und <math>b</math> aus der Teilmenge <math>U</math> auch das Produkt <math>a \circ b^{-1}</math> ein Element von <math>U</math> ist.<br /> | ||

| + | Setzen <math>b=a</math>, womit nach <math>\text{(*)}~ a\circ a^{-1} \in U</math> gilt. Wegen <math>a \circ a^{-1} =e</math> ist das Einselement <math>e</math> ein Element der Teilmenge <math>U</math>. | ||

| + | |||

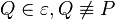

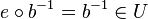

| + | =====Zeigen, dass mit <math>b</math> auch <math>b^{-1}</math> zu <math>U</math> gehört===== | ||

| + | Wegen <math>e \in U</math> (gerade gezeigt) und <math>b \in U</math> (Voraussetzung) gilt nach <math>\text{(*)}</math> <math>e \circ b^{-1} = b^{-1} \in U</math>. <br /> | ||

| + | <math>\text{(II)}</math> ist damit bewiesen. | ||

| + | |||

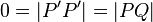

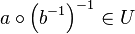

| + | =====Zeigen, dass die Verknüpfung <math>\circ</math> abgeschlossen auf <math>U</math> ist===== | ||

| + | Wir haben gerade gezeigt, dass mit <math>b \in U</math> auch <math>b^{-1} \in U</math> gilt.<br /> | ||

| + | Mit <math>a \in U</math> und <math>b^{-1} \in U</math> gilt nach <math>\text{(*)}</math> <math>a \circ \left ( b^{-1} \right ) ^{-1} \in U</math>.<br /> | ||

| + | Nach einem Hilfssatz aus der Vorlesung gilt: <math>\left ( b^{-1} \right ) ^{-1} = b</math> und damit <math>a \circ b \in U</math>, womit <math>\text{(I)}</math> bewiesen wurde. | ||

<!--- Was hier drunter steht muss stehen bleiben ---> | <!--- Was hier drunter steht muss stehen bleiben ---> | ||

|} | |} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[Kategorie:Algebra]] | [[Kategorie:Algebra]] | ||

Aktuelle Version vom 14. Juli 2018, 13:30 Uhr

Beispiele, GegenbeispieleBeispiel 1Wir gehen von der additiven Gruppe der Restklassen modulo 6 aus

Wir wählen aus

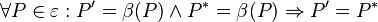

Beispiel 2Die Gruppe der BewegungenDie GruppenmitgliederUnter einer Bewegung

|

![[\mathbb{Z}_6, \oplus]](/images/math/9/0/d/90daaa2a8d1138539ff15f39a74f58c8.png) .

.

die folgende Teilmenge

die folgende Teilmenge  aus:

aus:

![[2\mathbb{Z}_6, \oplus]](/images/math/e/3/2/e32854e004ab70107710abac0af772d9.png) ist eine Gruppe und damit eine Untergruppe von

ist eine Gruppe und damit eine Untergruppe von  versteht man eine abstandserhaltende Abbildung der Ebene auf sich:

versteht man eine abstandserhaltende Abbildung der Ebene auf sich: unsere Ebene.

unsere Ebene.

bezeichnen.

bezeichnen.

.

.

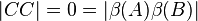

![[\Beta, \circ]](/images/math/0/d/b/0dbb39c2e6e24499e8dd3049f199a7df.png) ist Gruppe

ist Gruppe und

und  eine Bewegung ist.

eine Bewegung ist.

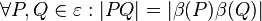

, die jeden Punkt die Abbildung der ebene auf sich selbst abbildet:

, die jeden Punkt die Abbildung der ebene auf sich selbst abbildet:

gilt natürlich auch

gilt natürlich auch  .

. und somit

und somit  .

.

bei

bei  hat.

hat. das Bild von

das Bild von  bei der Bewegung

bei der Bewegung  gibt, der durch

gibt, der durch  gibt. Dann gilt:

gibt. Dann gilt: und damit

und damit  , was ein Widerspruch zur Annahme

, was ein Widerspruch zur Annahme  ist.

ist.

und

und  aus

aus  abgebildet werden:

abgebildet werden:

müssen

müssen  . Unsere Annahme

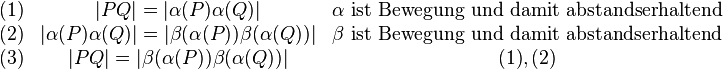

. Unsere Annahme  besitzt, heißt Drehung. Falls die Bewegung genau den Fixpunkt

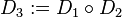

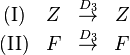

besitzt, heißt Drehung. Falls die Bewegung genau den Fixpunkt  die Menge aller Drehungen um

die Menge aller Drehungen um ![[\mathbb{D}_Z, \circ ]](/images/math/5/5/2/552d0d83fed54a94d1775beb5f9391f9.png) ist eine Gruppe:

ist eine Gruppe:

und

und  zwei Drehungen um

zwei Drehungen um  ebenfalls eine Bewegung. Weil

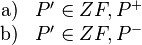

ebenfalls eine Bewegung. Weil  sein. Es können jetzt genau zwei Fälle auftreten:

sein. Es können jetzt genau zwei Fälle auftreten:

.

.

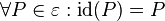

der Geraden

der Geraden  ist ein Fixpunkt bei

ist ein Fixpunkt bei  . Für das Bild

. Für das Bild

, woras folgt, dass jeder Punkt der Ebene bei

, woras folgt, dass jeder Punkt der Ebene bei  zu einer Bewegung

zu einer Bewegung  mit genau dem Fixpunkt

mit genau dem Fixpunkt ![[\mathbb{Z}_7, \oplus ]](/images/math/4/f/9/4f99ed9383011693e47f2407152b959a.png) und

und ![[\mathbb{Z}_7, \otimes ]](/images/math/3/e/6/3e625be0a151457aeba319347851fb4b.png) . Da wir bei multiplikativen Restgruppen das neutrale Element bezüglich der Restklassenaddition nicht berücksichtigen ist die Menge der multiplikativen Restklassengruppe modulo

. Da wir bei multiplikativen Restgruppen das neutrale Element bezüglich der Restklassenaddition nicht berücksichtigen ist die Menge der multiplikativen Restklassengruppe modulo  eine echte Teilmenge der additiven Restklassengruppe modulo

eine echte Teilmenge der additiven Restklassengruppe modulo ![[\mathbb{Z}_4, \oplus ]](/images/math/8/0/9/809eadba6a0a17ba00b6356273a6aade.png) ist bekannterweise eine Gruppe.

ist bekannterweise eine Gruppe. ![[T, \oplus]](/images/math/b/6/7/b67f906e0eb5b26fdf8bc244b095c477.png) mit

mit  ist keine Untergruppe von

ist keine Untergruppe von ![[G, \circ]](/images/math/4/6/8/4686bbf90bf7ebab892b288a31255920.png) eine Gruppe und

eine Gruppe und  eine Teilmenge von

eine Teilmenge von ![[U, \circ ]](/images/math/b/e/9/be91aec2753430c87cc11578aed000df.png) ist Untergruppe von

ist Untergruppe von  .

.

![~[U, \circ]](/images/math/7/8/2/782ef8008e3aad3a582c61112602da9d.png) ist genau dann Untergruppe von

ist genau dann Untergruppe von

gilt.

gilt.

.

.  .

.

sagt aus, dass mit

sagt aus, dass mit  und

und  aus der Teilmenge

aus der Teilmenge  ein Element von

ein Element von  , womit nach

, womit nach  gilt. Wegen

gilt. Wegen  ist das Einselement

ist das Einselement  zu

zu  (Voraussetzung) gilt nach

(Voraussetzung) gilt nach  .

.  ist damit bewiesen.

ist damit bewiesen.

gilt.

gilt. und

und  .

. und damit

und damit  , womit

, womit  bewiesen wurde.

bewiesen wurde.